This paper originally written as a discussion paper with informal citation.

ASH-3200: Ancient Near Eastern Societies

Dr. Tiffany Earley-Spadoni

University of Central Florida

|

| Nergal of Larsa |

Magic and Medicine in the Ancient Near East

For the people of

the ancient Near East, the use of magic and medicine may not have been considered

separate fields to be used exclusive of each other. In fact, evidence suggests that the two were

likely intermingled to such a degree that it would be impossible to conduct

“healing” without both interacting together.

While the details of the form and purpose of magic may have varied from

culture to culture or across time periods, the use of magic as a primary

component of “medicine” is evidenced in both ancient Mesopotamia and ancient

Egypt. Magic for the people of the

ancient near east was not only often used as a complementary therapy of medicine

but was also employed as a necessary component of medicine.

In

ancient Mesopotamia, the concept of healing often combined the practical with

the mystical (E-S, Healing). There could

be many causes of illness and harm, and many of these were collected together

into books of therapy. One such was the Surpu

(Akkadian for “burning”). This text

described a number of conditions and the related ritual spells to be performed

to rid the patient of the undesired harm (E-S, Healing). There were many things that could bring about

illness, disease, or misfortune. Across

the region we can find evidence of magic used to reverse common illnesses,

witchcraft, and epidemics. All forms of

ritual healing involved some basic formulaic components: a description of symptoms, a diagnosis of

cause, a ritual incantation, a ritual action(s), and often an appeal to a

higher power (Schwemer, Witchcraft). Illness

or harm was often not considered just a “physical” problem. There usually was a

dual component of the physical along with the spiritual or supernatural,

whether that be divine, demonic, or witchcraft.

Therefore, healing necessarily included, as Earley-Spadoni indicated

earlier, both the practical and the mystical.

Sometimes the divine could be responsible for harm, as in the case of

the Hittite definition of epidemics, called the “devouring of God” found in the

Mari letters (Attia, Epidemics). At

other times, the demonic or spirits could be the culprit, as well as spells

cast by witches or warlocks. Common to

the healing component in both Mesopotamia and Egypt were the use of spells

(incantations) along with a physical relic of some sort: figurines, images, statues, stela, symbols,

and, especially in Egypt, names, and amulets.

The

belief in supernatural and magical forces in ancient Egypt often involved the

divine both in cause and solution more than it did in Mesopotamia. It goes to say that those solutions to

illness likewise entered more into the realm of the gods and goddesses. However, the magical formulation of spells

and actions were often very similar between the two. Like the Mesopotamians, the Egyptian ritual

formula for healing included the description of symptoms, diagnosis of cause,

ritual incantations and actions, and appeal to a higher power. In Egypt, magic, heka, was one of the

main forces used in the creation of the world (Pinch, Magic). Priests were the main practitioners of magic

and Sekhmet, the goddess of plague, was also the primary deity of healing. Lector priests were the considered the

highest users of magic, then, in descending primacy, came the scorpion-charmers,

midwives and nurses, and “wise women” (Pinch, Magic). There was a strong sense in Egyptian ritual

magic of the power contained in the word.

So much so that not only was there power in the spoken spell or

incantation, but also the written word.

Often, protective or healing spells were written into amulets that were

worn or written onto papyrus which were folded and worn, both for protection

and healing. In addition to the standard

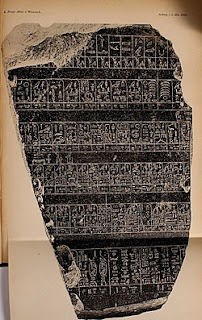

ritual magic and protection spells, were the use of stela to transmit healing

power. This was often found on a cippus,

or stela with the image of the infant god Horus. Upon the stela were written various healing

spells. Water was poured over the stela

and drunk by the patient. It was

believed that the patient was then imbued with the healing power of the spell (Pinch,

Magic). Other practices related to

healing in ancient Egypt included the use of oracles, especially in relation to

the god Amenophis (McDowell, Religion, pg. 93), and the importance of household

cults dedicated to deceased ancestors, as evidenced in the worker’s community

at Deir el-Medina (McDowell, Religion, pg.104). Both of these were important components

related to healing. The use of oracles

was often employed to find out the cause of misfortune. And it was not uncommon for the living to ask

dead relatives to implore the gods for their intervention.

As

we can see, magic was a common and important component of life and healing in

the ancient world. As Tzvi Abusch

implies in The Witchcraft Series:

Maqlu, in both Mesopotamia and Egypt, magic was a “legitimate enterprise

as part of state religion” as well as accepted culture. She goes on to specify that while there was

those who practiced “black magic,” these were generally prohibited. A telling indicator of something that was

“missing” from the Mari archives, as noted by Attia in Epidemics in

Mesopotamia, is the conspicuous lack of request for doctors. Instead, in epidemics and other illnesses, what

was requested was exorcists and divinators.

The use of magic in the ancient Near East was not only a primary

component of healing, but I would also argue an indistinguishable part of medicine. The people of this time would not have

separated magic from medicine as two distinct fields.