This paper originally written as a discussion paper with informal citation.

ASH-3200: Ancient Near Eastern Societies

Dr. Tiffany Early-Spadoni

University of Central Florida

|

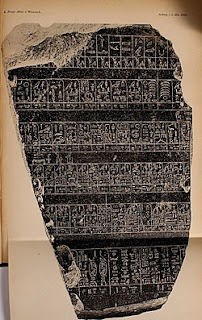

| Palermo Stone |

Primary Sources for the Study of Ancient Egypt

When discussing the history of

ancient Egypt, we have several types of sources to pull from in gathering

information. Unfortunately, the only

full “historical” analysis that we do have is from Manetho, an Egyptian priest

living in the 3rd Century BCE.

Modern scholars must use care in using Manetho as a source as, obviously

he is so far removed from the earliest periods of Egyptian history, but also

due to several other reasons. One, his

history was severely abridged by Christian writers several centuries after it

was written. Secondly, according to

scholar William Murnane, Manetho was never able to distinguish within his

sources those that were more factual and those that were mythical. Add to this the fact that Manetho did not use

comparative analysis with other source materials such as inscriptions written

during the time period being discussed (Murnane, The History of Ancient

Egypt, pg. 691). Most of our primary

source data comes in the form of hieroglyph inscriptions, used from some of the

earliest writings throughout the ancient period. Hieroglyphic inscriptions were used almost

exclusively in the context of monumental art and architecture, such as

dedicatory inscriptions and commemorative texts and often reflected a state

ideology (Early-Spadoni, Sources in Ancient Egypt). In addition to monumental texts, we also

have, though scant in number, writings on papyri. Papyrus texts were written on the leaves of

the papyrus plant that grew along the Nile River. Typically, in these and other non-formal

inscription texts, the form of writing used was Hieratic, a cursive form of

Egyptian. Because the papyrus does not

hold up well over time, we have far less of these as archaeological artifacts

than what we have from the Mesopotamian archives. These texts often reflect a variety of genres

including contracts, legal texts, and religious texts (Early-Spadoni, Sources). One of the more interesting artifacts we have

from the Early Dynastic period is the Palermo Stone. The Palermo Stone was written inscribed

during the 5th Dynasty and gives us a list of kings reaching back

into the pre-Dynastic, and mythical, past (Murnane, History, pg.

693). According to a transcription of

the Palermo texts by Heinrich Schafer, the division of registers and vertical

lines depict the year-by-year reigns of kings along with significant events

during each reign. We also find the

height of the Nile flood for each year (Schafer, Ein Bruchstuck

Altagyptischer Annalen). Along with

inscriptions from royal tombs, palaces, and temples, and particularly

increasing in later years, we have numbers of letters of correspondence between

Egypt’s Pharaohs and the rulers of other large and small empires to the

east. It comes as no surprise that the

most secure we can feel in the historical accuracy of an event is when two

unrelated documents corroborate each other such as in the raid of the 22nd

Dynasty’s Shoshenq I into Palestine.

This event is recorded not only on a triumphal relief in the Temple of

Amun at Thebes, but also attested in the Hebrew Bible in the book of 1 Kings

14:25-26 (Murnane, History, pg. 710).

The

form, style, and context of writings and artifacts can often shape our

interpretation of their source in unique ways.

Given the multitude of monumental architecture related to burial and the

dominance, particularly in the earlier periods, of texts that are funerary and

mortuary related…that is, they are often related to death and the rituals

surrounding death (Early-Spadoni, Sources), it can be easy to assume that

perhaps the culture only left writings related to these events or that perhaps

they were overly consumed by them.

However, it is important to remember that what artifacts we have are

often those that are best preserved over time, not necessarily those that were

most produced. One of the interesting

facets about Egyptian culture is in how they named cities, places, individuals,

and cultures. We can often gleam some

information from this. During the 1st

Dynasty, kings often carried simpler names such as Narmer (“Baleful Catfish”)

or Aha (“Fighter”). In the 2nd

Dynasty, we see a transition to names that we may be able to attribute to a

stronger sense of relating the person of the ruler to that of the divine, such

as the boastful title “He Who Belongs to the God” which is the interpretation

of the name Nyjetner (Murnane, History, pg. 695). As is often the case, writings from the

ruling class often included or reflected an ideological or political

message. In an essay of political

propaganda, Life of Neferti, the 12th Dynasty’s Amenemhet I

portrays himself as “a national savior, coming after a period of protracted

chaos” (Murnane, History, pg. 699).

As

in all source material from any period, there are limitations to what we can

know for sure about their historical accuracy as well as their historical

completeness. As in the case of

Mesopotamian sources, we often do not see a picture of the lives of the common

workers, women, children, and slaves. We

often only see what the ruling class, the elite officials, and the religious

elites want us to see. There are some exceptions,

however. Take, for example, ostracon

found in the workers’ community of Deir el-Medina. The inhabitants here wrote on ostraca, broken

pieces of pottery, and of the hundreds of texts found, many ranged from love

songs to laundry lists, and other everyday writings (Early-Spadoni, Sources). Further insight can be gained in the exchange

of correspondence between Amenhotep III and King Tushratta of the Mitanni as

well as King Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon.

In both cases, the eastern kings requested a daughter of the Pharaoh for

marriage. Amehhotep replied that for all

it’s history, no daughter of Egypt has ever been sent off for marriage

(implying political marriage to other kingdoms) (Murnane, History, pg.

704). While this on the surface seems

noble, we do not see the full picture that Amenhotep himself received foreign

daughters as brides. And, finally, in

discussing the limitations of our sources, I want to briefly mention both the Story

of Sinuhe and The Execretion Texts, both from the 12th

Dynasty. While both writings give us a

picture of an Egypt that was both wary of potential enemies to the east, but

also not desirous of making war there with the intent of establishing or

expanding empire (Murnane, History, pg. 700), we also can come away

short because we do not fully understand why this is the case. Could it be that the ruling class had no

desire to expand or make war? Were there

internal conflicts that prevented such actions?

Was the country experiencing economic hardships that forced it to look

in upon itself and ignore the rest of the world? These are questions that are not easily

answered and can affect how we envision the status of the ancient Egyptian

world during that period.

No comments:

Post a Comment